by Seth Carden

The East African Rift System (EARS) is one of the most intriguing geologic sites in the modern world. Throughout the section of Eastern Africa, tectonic activity has created cracks in continental crust known as rifts, such that a section of the Nubian plate has started to break off from the main plate. The EARS is not a singular area where rifting is taking place but a complicated series of rifts stretching from the Red Sea to the African Great Lakes region. Scientists are fascinated with this region because it is one of the only active rift zones on the planet.1 The EARS has provided them with a great opportunity to collect field data on the movement of plate tectonics, a process that is critical in understanding why the Earth looks the way it does today.

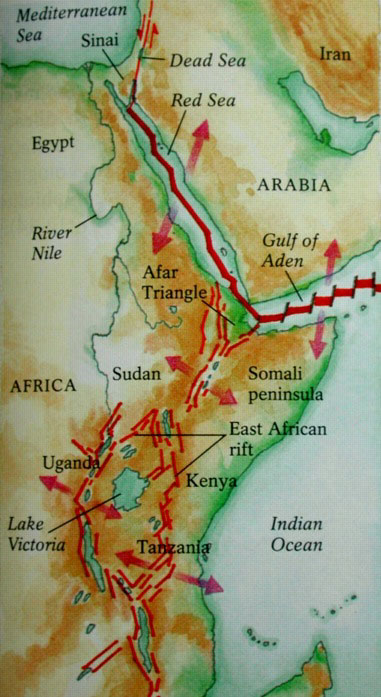

The map highlights the two main sections of the EARS: the Ethiopian Rift and the East African Rift. Oftentimes, individual rifts have been given different names (ex. the Nyanza Rift near Lake Victoria) but they all fit into these two regional categories.

Source: geology.com

Sections of the EARS

The East African Rift System contains two distinct rift zones. The main section is called the Ethiopian Rift. The Ethiopian Rift is wider and further along in the rifting process, leading scientists to believe that the tectonic activity in this region has been going on for a while. It is mainly located in the Afar region of Ethiopia where the Red Sea meets the Gulf of Aden.

The second rift zone is composed of two large rifts that flank the sides of Lake Victoria. These rifts together make up what scientists call the East African Rift. The EAR is located south of the Ethiopian Rift, extending into Kenya and parts of Tanzania. The Western Branch (also called the “Albertine Rift” due to its proximity to Lake Albert) mostly cuts through the Great Lakes region to the west of Kenya. The Eastern Branch is almost directly across from the Western Branch, cutting straight through Kenya just west of the capital city, Nairobi.1

Plate Tectonics and Divergent Boundaries

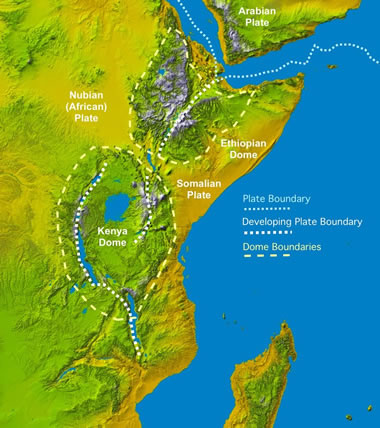

The map shows the many divergent boundaries that occur in the region of East Africa. It highlights both older boundaries that have formed the Ethiopian Rift and the new boundaries that are beginning to form the East African Rift.

Source: geosci.usyd.edu.au

The driving force behind the creation of these rift zones is the science of plate tectonics. The Earth’s lithosphere is divided into different tectonic plates that vary in size and are constantly moving, shifting, and grinding against each other. Because these plates are made of hard, rigid crust, they tend to cause catastrophic events when they collide together or drift apart. The area where two tectonic plates come together is known as the plate boundary. In East Africa, there are two main plates: the African (or Nubian) Plate, and the Arabian Plate, which are separated by a divergent plate boundary. These plates began to move apart a long time ago, forming a large rift valley between East Africa and the Arabian peninsula. This valley has already filled with water, creating what are known today as the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden2 (see Figure 2).

However, this boundary is no longer the only one in the area. Further south, multiple smaller divergent boundaries have begun to form within the African plate itself, separating it into two blocks: the Nubian block to the west and the Somalia block to the east (see Figure 2). If the spreading here follows the course of its predecessor to the north, it is likely that these rift zones will also fill with water and create a channel between the Nubian and Somalia blocks that will act similarly to the Red Sea.2 In fact, the Western Branch has already begun to fill with water. In addition to the large rifts, there are smaller features known as grabens which act like mini rifts themselves. They often are just branches off from the main rifts, but some are large enough to have been given their own names (ex. the Nyanza Rift near Lake Victoria).1 These grabens are not their own separate areas of divergence but are a product of the system as a whole.

The Triple Junction

The map shows the two protruding regions known as the Kenya Dome and the Ethiopian Dome. At the triple junction, three rift zones formed: one which is now the Red Sea, one that is the Gulf of Aden, and one that is the East African Rift

Source: geology.com

It is difficult to know for sure what caused these plates to start drifting apart, but scientists believe it is related to an elevated magma chamber that lies below the lithosphere. As it grew nearer to the surface, the magma caused the crust to become dome-shaped in two different areas: the aforementioned Afar region of Ethiopia and central Kenya (see Figure 3). This process first began in the Afar region. As the crust expanded, it started to break because the outer lithosphere is brittle. Early on, these fractures began to form small grabens around the domed area, but as the crust protruded further outward, larger fractures formed. Eventually, three rift zones formed in a pattern geologists call a “triple junction”1.

A triple junction is a point at which three tectonic plates intersect. At these points, the three plates either converge, diverge, or scrape against each other. When all three plates are moving away from each other, just as they are in the Afar region, ocean ridges are being formed between them. At most places in the world where this occurs, it happens below sea level, so it is less noticeable to humans. However, in East Africa, the triple junction is partially above sea level, which is why scientists are so intrigued by what is happening there.3

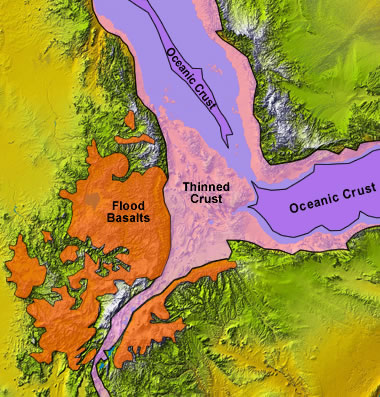

Here the triple junction of Ethiopia is shown. The flood basalts (orange) have combined with the continental crust (yellow) to form the thin hybrid crust (pink). In the Gulf of Aden, and a little bit in the Red Sea, oceanic crust (purple) has started to form and a new ocean basin is being created.

Source: geology.com

When the rifts were in their preliminary stages, before the plates began to separate, there was a large amount of volcanic activity around them. Unlike traditional volcanoes, the rifts behaved sort of like a flooded river, but instead of water, it was lava that flowed over the sides. The eruptions often spread over huge amounts of land and are known by scientists as “flood basalts”. As the crust began to stretch further, the continental crust mixed with the cooled basaltic lava and formed a very thin hybrid crust, which progressively dropped until it was below sea level. Water then filled the area that is now the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, and as the plates stretched even further, oceanic basalts erupted through the thin hybrid crust and began to form new oceanic crust1 (see Figure 4). Over large periods of time, more and more oceanic crust will form, and the space between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula will grow larger. If the spreading continues at its current rate, the expanse that is currently the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden will eventually become an ocean that will further separate the two continents.

The Continental Rift Zone

South of the Afar region, the processes that have caused the East African Rift to form are likely similar, but they do have some key differences, the first being that the spreading does not occur at a triple junction. The rift zone does not occur between multiple plates, rather it is consolidated to the African continent. Therefore, the rifting here is called “continental rifting”. Another key difference is that the spreading processes at the EAR is not as far along as it is at the Ethiopian Rift. This is evidenced by the fact that there are still grabens located throughout the landscape of central Kenya. Because it appears that the spreading process there has not progressed to the point at which the spreading at the triple junction has, scientists have been able to observe what the preliminary stages of the Ethiopian Rift might have looked like.1

The development of the EAR is unique, however, because there are two distinct branches that break off from each other, flanking Lake Victoria (Figure 2). Geologists believe the continental rifts have formed this way because they occur along the sutures that were formed when ancient land masses collided to form what is now the continent of Africa. The reason the rift system split is because the rock material surrounding Lake Victoria is made of ancient metamorphic rock that the rift was unable to cut through because it was so hard. Otherwise, scientists believe that the EAR works just like the Ethiopian Rift. There appears to be a magma chamber that is causing a dome to form in central Kenya, implying that the spreading process will be quite similar to the process that occurred in the Afar region.1

Effects on Society

Source: nytimes.com

As one might imagine, the East African Rift System often endangers the lives of many people who live close to it. Due to the fact that the EARS is composed of many small normal faults, the area is prone to earthquakes. However, the volcanic activity around the rift zones has been a much bigger problem, especially for the inhabitants of Kenya. Not only do the rift volcanoes fill the air with toxic gases, but they have covered the ground with volcanic ash. It may not seem like an obvious hazard, but during flood periods, volcanic ash can be a huge issue. Because it is hard for many architects to tell that the foundation for their future building is made up of ash, they often do not know their building is on unstable ground. During great periods of flooding, the large amounts of water cause the ash to destabilize, and the buildings on top of it collapse.4

Kenya has a history of buildings collapsing unexpectedly after long flood periods. Most recently, in December, a six-story apartment building collapsed in Nairobi, causing four people to lose their lives. However, this incident was not isolated. Just three months prior, a Nairobi school building collapsed, killing seven students. An even worse collapse in 2015 killed over 50 people. It is estimated that 132 people have died from incidents like these and almost 160,000 have been impacted by them.5 Many times, this has lead people to speak out against the government, blaming the collapses on shoddy building materials and oversight. However, because these collapses seem to happen particularly after large rain events, they likely occur due to the destabilization of the ash foundations.

The Future of the EARS

Source: https://www.arcgis.com/sharing/rest/content/items/52910977b1684a348a350bc1c78394ce/resources/1573757099269.jpeg?w=2805

After studying the spreading process at the Ethiopian Rift and the East African Rift, many scientists believe that the African continent will completely split along the EAR, creating two separate continents. If the rifting keeps following its current trend, the EAR, which is already 3700 miles long, will eventually make a vertical cut that reaches all the way into South Africa. Then, just like what has happened at the Ethiopian Rift, ocean crust will begin to form and a new ocean basin will separate the Nubian block from the Somalia block, creating a new continent that will move progressively toward South Asia as spreading continues. This new continent will contain parts of what is now Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Mozambique. Thankfully for the people that live in these countries today, it will take about 50 million years for the spreading to progress to this point.6 The entire continent of Africa will not split in two in a matter of hours; however, as discussed before, the EAR will continue to affect the lives of the people living near it in the short run as well.

Conclusion

The East Africa Rift System is a natural phenomenon that has greatly helped scientists learn more about the movement of plate tectonics. Because the separation of continents can be clearly seen there, scientists have been able to analyze the EARS to get an idea of why all of the continents look the way they do today and to project how they might look in the future. As the science of plate tectonics becomes more easily understood, the more we will know about the formation of our beautiful planet.

Sources

1. Wood, James, and Alex Guth. “East Africa’s Great Rift Valley: A Complex Rift System.” Geology.com, geology.com/articles/east-africa-rift.shtml.

2. Reichard, James S. Environmental Geology. Mcgraw-Hill, 2018.

3. Alden, Andrew. “What Happens When Three Tectonic Plates Collide?” ThoughtCo, 18 Feb. 2019, www.thoughtco.com/triple-junction-1441120.

4. Gibbens, Sarah. “Why This Giant Crack Opened Up In Kenya.” National Geographic, 3 Apr. 2018, www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2018/04/east-african-great-rift-valley-crack-spd/.

5. Dahir, Abdi Latif. “Building Collapse in Nairobi Leaves at Least Four Dead, 29 Injured.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Dec. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/12/06/world/africa/kenya-building-collapse-nairobi.html.

6. “A giant crack appeared in the ground in Kenya, seemingly overnight.” CBS News, 4 April 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RG-wx-KYnTk.